How does an industrial, hardware-oriented region – that has the research-driven electronics corporation Philips to thank for its growth – continue to be relevant in an area of open innovation and digitisation? This question took centre stage in the round-table discussion that Link Magazine organised with design and innovation firm VanBerlo in Eindhoven at the end of last month. ‘Co-location’ proves to be one of the keywords: scientists, designers and engineers working together on innovation – as in the Innovation Powerhouse, where the round-table discussion was held, or in the Eindhoven Engine. This new initiative wants to have knowledge institutes and industry work out solutions to major (social) challenges together.

Panel chairman Ad van Berlo

Round-table discussion about the focus on the customer and collaboration within the ecosystem

The Eindhoven Brainport region has Philips to thank for its rise as an industrial hot spot in the Netherlands. The electronics corporation covered a wide range of sectors, driven by the Philips Natlab. Lots of spin-offs, with lithography machine builder ASML being the largest, continued to build on that. Divisions such as Semiconductors and Lighting have been spun off and Philips now profiles itself as a health technology company; its research has been ‘narrowed’ accordingly. Panel chairman Ad van Berlo expresses his concerns about that: ‘What does that mean for the region? Many start-ups have gained their initial experience at Philips. How do we foster that research?’

Eindhoven Engine

Maarten Steinbuch, professor of control technology at TU/e and entrepreneur with Eindhoven Medical Robotics, shares his concerns. ‘Universities play a role in that as the ‘long-term conscience’ for innovation.’ This prompted him to launch the Eindhoven Engine initiative: a new ‘Natlab’ where academic researchers and industrial engineers work together – on a co-location basis – on innovative projects en start-ups. TU/e is now elaborating the concept; the intention is that other knowledge institutes and major companies participate in it and that 500 people will work there in projects eventually. Steinbuch draws inspiration from the student teams that develop and build innovative systems – such as a solar car or electric motor, often for taking part in an international competition – with a great deal of enthusiasm and in a short period of time. ‘Why would this be impossible with teams of ‘seniors’? The Knowledge Workers Granting Scheme has shown what the result can be.’ He refers to a scheme that the government introduced in 2009: knowledge workers employed by companies that were in dire straits at the time of the crisis could be temporarily stationed at a university or other knowledge institute, paid by the government. ‘In this spirit we now wish to bring young university graduates and people from industry together in the Eindhoven Engine to work on projects that are – preferably – linked to social themes.’ Steinbuch refers to the major challenges that the EU has formulated for the 2020 Horizon research programme. ‘There, I opt for the task of combining industrial technology with digitisation and artificial intelligence (AI). The key question for a hardware-oriented region such as ours is how we can cope with the acceleration induced by digitisation and AI. We are now pooling project ideas.’ This challenge not only faces hardware companies but Van Berlo as well, according to innovation strategist Ivo Lamers. ‘As a design firm, we must join the global digitisation. We’re also occupying ourselves with the rise in robotics and have hired the first people for AI.’

Of course, the region is already active in the area of open innovation, also on a co-location basis, Steinbuch knows. He mentions the collaboration between the Máxima Medical Center in Veldhoven and Philips on healthcare innovation and the Holst Centre in Eindhoven, the open-innovation R&D centre of TNO and the Belgian imec. However, as the next big step, the Eindhoven Engine is supposed to scale up open innovation.

From right to left: Kees Gehrels, Valer Pop en Ivo Lamers. Foto Bart Overbeeke

User in the picture

The transformation that the region is undergoing from closed innovation, as in the Philips Natlab in the old days, to open innovation, for example at the High Tech Campus Eindhoven and soon in the Eindhoven Engine, must gain momentum. A great deal is expected of the spin-offs and start-ups. Ad van Berlo wants to know what their success factors are. Focus and passion, says Valer Pop, CEO of LifeSense Group (25 employees). In 2015, after having worked at the Holst Centre for ten years, he started his own company, which is now developing a training solution for women with incontinence problems. Smart underwear is fitted with sensors that detect activity and loss of urine, and based on the combined information, an app can advise the women about their training and encourage them by showing progress. ‘We can lose a customer within eight weeks, as seventy percent of the users will have been relieved of the problem by then. But there are as many as 200 million prospective customers worldwide.’ In other words, it is a promising technology and business case. Focus is an important element in developing it, according to Pop. ‘Given that possibilities abound, especially in the technological field, you have to make the right choices. A start-up relies on technology, design, business model and capital, but I often miss that combination at start-ups. Our ambition is to become the new Philips, but in a different way.’ The prospects are good, because the patented innovation has won many prizes and has been successfully introduced in various countries. And Pop has managed to attract the necessary substantial investments for scaling up. A key success factor was finding one hundred women with incontinence problems who started testing the product.

Mixed feelings

Ad Vermeer can relate to Pop’s story. He is the inventor of the world’s first selective asparagus harvester, which automates the uncomfortable manual work of cutting asparagus and increases the yield. Cerescon, the company that is marketing the machine, is not the first start-up he has been involved in. Last month, after years of development, Cerescon (25 employees) delivered its first machine to a paying customer. ‘We have already had a user group, including asparagus growers, involved in the development for three years. It is surprising how they sometimes come up with other solutions than we can think of.’ Vermeer is now also seeing opportunities for selective harvesters for other crops, for which collaborative research needs to plant the seed. He has already received subsidy from Horizon 2020.

Talking to customers, and to their customers, is something Kees Gehrels does constantly as well. As senior director of new business at NXP Semiconductors, a Philips spin-out, he is developing the automotive market, where NXP is global market leader with its chips. ‘My focus is ADAS, advanced driving assistance systems, for which we expect enormous growth in the coming years.’ NXP serves Tier 1’s, the major system suppliers in the automotive industry, but it is ultimately about what their customers – car manufacturers – expect. ‘That is why we talk a lot to the customer’s customer. Our direct customers sometimes have mixed feelings about our close contact with their customers, but we need to understand what those end customers exactly want. We do this as far away as China, where we also talk to OEMs, as they are growing very fast.’

Maarten Steinbuch(Left) and Ad Vermeer

Philips heritage

With its innovations, the Brainport region is in a position to contribute to global growth, but there are some challenges to overcome. For example, international marketing is needed in order to attract real top talent to the region and the now somewhat modest presentation of the region may also be slightly ‘bolder’. It already begins with the start-ups that have to work on their pitching skills; that just does not come natural to technologists. There is a bottleneck for the region, according to Van Berlo. ‘Innovation will not become a success until the business is involved.’ He therefore raises the question of whether the policy for start-ups could do with a few changes. ‘The term ‘start-up’ is strongly associated with young people and technical ideas. There are two problems there’, Ad Vermeer explains. ‘First of all, it is not about the technology, it is about the customer’s problem. Secondly, young starters sometimes fail because of their lack of experience. You need a combination of young and older people.’ Van Berlo refers to a study that demonstrates that the best start-up entrepreneurs are aged 40 and over. You need a mix of the Philips DNA and young people, says Kees Gehrels from NXP. ‘That’s why the Eindhoven Engine is such a cool initiative. It should become somewhat more concrete though, with more focus, on a sector such as the automotive industry, for example.’ Maarten Steinbuch acknowledges this and points to the opportunities that the Philips heritage offers. ‘Everything in the region has ties with that heritage. We need to utilise that experience in conjunction with the input from young people, who have a feel for design and have mastered an agile way of working.’ Ad Vermeer: ‘We need to combine the strengths of Philips with enterprise, which the company lacked too much. By making the cross-over from high-tech to agricultural, we have seized one global challenge (global food supply, ed.).’

Production in the Netherlands

For the policy concerning start-ups, Valer Pop once again points to the well-known success formula of ‘knowledge + skill + cash’. ‘There is plenty of knowledge and skill here in the region, but ‘cash’ is a problem. There are few venture capitalists (VCs) here; more venture capital from private investors is needed.’ There proves to be little interest among the round-table participants to do business with VCs, because most of them are used to investing in software start-ups, who are able to launch their first product quickly and then scale up rapidly, so that the investor can be given a nice exit within a few years. Ad Vermeer says, ‘A hardware-related start-up calls for a different type of investor, one with more patience. Hardware has a development cycle of three years, which often forms too high a threshold to go on board. However, once you have achieved success, that disadvantage becomes an advantage: that threshold also applies to competitors that want to follow in your wake.’ Where many of software start-ups dream of an exit, the round-table participants are barely interested. Maarten Steinbuch says, ‘I don’t believe in an exit. For Eindhoven Medical Robotics we contacted private investors. We want to grow to a 1,000 strong workforce in ten years from now and we want to have our robots manufactured in the Netherlands.’ The latter is also what Valer Pop aims for, but he advocates a global marketing approach. ‘That international approach has helped us a lot.’ At the same time, Eindhoven is also internationalising, says Kees Gehrels: ‘We have a 35 strong team for Automotive Radar here, with twenty different nationalities. That works wonders.’ According to Ivo Lamers, not only the highly educated talent that the region needs merits attention. He says, ‘We must not forget all the people working in the factories when everything is being robotised. They must be involved in the developments.’

Innovation Powerhouse

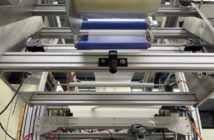

The round-table discussion was hosted by Ad van Berlo, founder of design and innovation firm VanBerlo, which moved into the Innovation Powerhouse in Eindhoven. This building is part of the heritage of the Philips corporation and was erected on the Strijp-T industrial estate in 1953 as a power plant for the Philips factories. On VanBerlo’s initiative, the property – building TR – was recently transformed into a high-profile business centre for innovative enterprises.

The ambition is to create an ecosystem for innovation, with Van Berlo guarding the formula, which he describes as follows: ‘A living lab for design, architecture, high-tech hardware and software, finance, big data, patents – these kinds of disciplines.’ The Innovation Powerhouse and the area around it on Strijp-T is home to start-ups, innovative companies such as Additive Industries, the builder of industrial 3D printers, and educational institutes such as Fontys University of Applied Sciences and Eindhoven University of Technology (TU/e). The building does not accommodate ‘traditional’ companies such as the large consultancies that are keen to set up shop in the area on account of its ‘hip’ look and feel. The commercial operation of the property requires a different, more long-term-oriented approach than the traditional ‘quick win’ approach. ‘A family that has operated in the property sector for sixty years bought this building four years ago after I had won them over to this new way of thinking. I really respect the way they opened their minds to this.’ Innovative is also the way in which the municipality of Eindhoven collaborates with the initiators and entrepreneurs on redeveloping the area. ‘The municipality is expected to fulfil mainly a facilitating role and allow the entrepreneurs to take part in the decision-making process. This is not an easy switch for the municipality to make, but the way they participate is commendable.’