Theme: Innovative business models for Dutch high-tech

Suppliers are looking for routes to more independence, to bigger margins. But the routes available vary considerably. Some head down the road towards their own module while remaining closer than ever to their customer. That way, the customer feels comfortable relinquishing its demand for a second source and the supplier gets the opportunity to make parts of the client-specific technology available to other customers. The third group of suppliers is not interested in having their own modules or technology and instead continue doing their thing the way they have always done. But they no longer do it alone: they form a community of suppliers in order to develop and manufacture the product together. By international standards, Dutch industry is small in scale. Cooperation is in its DNA, in order to survive. And it is precisely that quality which is being used to become more independent.

Suppliers on the road to maturity

Dutch industry has always led the way internationally in terms of outsourcing at a high level. So it is no coincidence that a new type of supplier is emerging here which operates so high up in the chain that you can hardly still call it a supplier. This new supplier is given complete responsibility for the development and production of a module and – up to a certain point – the opportunity to use that module to serve a global market. This type of collaboration calls for the highest degree of openness and trust between customer and supplier in both directions. But it also calls for scale and proactiveness on the part of the supplier. In practice, all of these requirements are tough to fulfil.

ASML’s need for more OEM-type suppliers

‘We need more OEM-type suppliers who can take responsibility for engineering, production, maintenance and services.’ So said CEO Peter Wennink during ASML’s All Employee Meeting at the end of January. It is a desire which has long been felt by the chip production machine manufacturer but is now being expressed openly. The same goes for parties such as Philips Healthcare and FEI Company; in order to cut costs and increase quality and innovative capability, these OEMs need suppliers that can do much more than simply faithfully carrying out what the customer has developed in detail.

Tipping point passed

Many Dutch suppliers are still performing that ‘old’ build-to-print role. Some of them, such as NTS and VDL ETG, have already got to a stage at which – based on functional specifications – they can engineer and upgrade a module (build-to-specification). But the next step, to an OEM-type company that develops/further develops complex modules entirely by itself in a proactive manner, based on its own knowledge of what the market wants, has been taken by only a few Dutch suppliers, says Paul Schuurmans of Praetimus consultants. ‘Of course, this step, to build-to-roadmap suppliership, is not an easy one. Companies like VDL ETG and NTS are the front-runners in that regard, but they haven’t got  there yet. Because you need to pass a tipping point after which you are no longer developing in response to customer requests but for the market as a whole, without there being a concrete order. That calls for a change in culture which is far from easy to accomplish and therefore demands complete commitment on the part of management. Because suddenly you need to start hiring developers and marketeers, you have to set up a global sales and distribution apparatus and start doing after-sales support. It is not uncommon for a firm’s history, its legacy as a service-providing, customer-focused supplier, to get in the way.

there yet. Because you need to pass a tipping point after which you are no longer developing in response to customer requests but for the market as a whole, without there being a concrete order. That calls for a change in culture which is far from easy to accomplish and therefore demands complete commitment on the part of management. Because suddenly you need to start hiring developers and marketeers, you have to set up a global sales and distribution apparatus and start doing after-sales support. It is not uncommon for a firm’s history, its legacy as a service-providing, customer-focused supplier, to get in the way.

In addition, financial clout and scale are essential. ‘Parties such as ASML are also looking for scale: if they are going to give you complete responsibility for developing a particular module as a business-to-roadmap supplier, they’ll want to be sure that you won’t go to the wall when you encounter the first dip. So you must never be dependent on a single OEM for more than 20 to 25 per cent of your turnover. And that in turn means that as a supplier, you are able to identify a market which is big enough for you to earn back the whole of your investment. A company like VDL ETG needs to find a lot more customers than just ASML for its wafer handler or the motion control technology incorporated in it. And of course that too is not so simple.’

OEMs are not consistent

But there are other barriers, points out Schuurmans in a white paper (see text box): OEMs are not always consistent. ‘They are keen to establish long-term strategic relationships with their suppliers, but that desire is not always consistent with the working methods of their own purchasing departments, which are often inclined to go for the lowest price. That means suppliers are not given the financial room to develop into build-to-roadmap suppliers.’ And is not just on the money side where things tend to go wrong; even before then, suppliers may not be given the necessary space to develop. When push comes to shove, OEMs may not accept a more or less standardised module – because they don’t want to ‘engineer around it’, they end up making all kinds of customer-specific demands. As John van Soerland of Phillips Healthcare previously admitted in Link: ‘When we hand responsibility to our suppliers and demand cost reduction proposals, we have to be prepared to adjust our products accordingly.’ Schuurmans: ‘On the one hand, OEMs like to see suppliers take the step to full independence and to grow. On the other, they don’t want the same suppliers to grow so big that they can start making demands, such as negotiating a particular price and retaining intellectual property (IP). OEMs can’t make the same demands of a big German supplier with a turnover of billions such as Zeiss or Trumpf as they can of a company like Frencken or NTS.’

A position like Zeiss

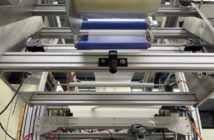

One company that wants to acquire a build-to-roadmap position is VDL ETG. CEO Simon Bambach is able to clearly indicate the size of the market for the wafer handlers his  company is now able to develop, manufacture and maintain and service. ‘We see opportunities particularly among medium-sized firms in semiconductors, and then you’re talking about a global market worth several billion euros.’ VDL ETG has managed to secure a corresponding position for itself as a supplier for ASML – in the role of ‘OEM white box’, as the chip machine manufacturer puts it. Over two years ago, the two firms launched a wafer handler pilot project. Once the required knowledge and skills had been transferred from the OEM to the supplier, ETG was also given complete responsibility for functional development. To clarify: ‘white box’ refers to the fact that the complete package of drawings for the wafer handler, which is being developed and built specifically for ASML, becomes the property of that customer. ‘But of course we are free to take the background knowledge we acquire within the company by developing at a functional level and use it for third parties too. The boundary between the foreground knowledge of ASML and our background knowledge is still somewhat diffuse. The fact is that ASML has made a conscious decision to transfer knowledge and skills to us which we can use more widely, precisely to enable us to enrich them with experiences elsewhere. And of course also to reduce the development costs for the wafer handler by allowing us to use that experience for the benefit of other customers.’ However, the final objective has not yet been achieved, notes Bambach: ‘We are now the only supplier with that knowledge of wafer handlers, so it is understandable that ASML still wants to have detailed financial control. But that is a question of time – trust needs to continue to grow on both sides. Our objective is to grow towards a position like that enjoyed by Zeiss SMT. Towards the type of partnership you already see in aircraft manufacturing. There, an OEM like Boeing has the know-how regarding the overall architecture of the aircraft and sufficient knowledge about matters such as the landing gear, the cockpit and the engines in order to be able to specify its requirements towards specialists such as Rolls-Royce.’

company is now able to develop, manufacture and maintain and service. ‘We see opportunities particularly among medium-sized firms in semiconductors, and then you’re talking about a global market worth several billion euros.’ VDL ETG has managed to secure a corresponding position for itself as a supplier for ASML – in the role of ‘OEM white box’, as the chip machine manufacturer puts it. Over two years ago, the two firms launched a wafer handler pilot project. Once the required knowledge and skills had been transferred from the OEM to the supplier, ETG was also given complete responsibility for functional development. To clarify: ‘white box’ refers to the fact that the complete package of drawings for the wafer handler, which is being developed and built specifically for ASML, becomes the property of that customer. ‘But of course we are free to take the background knowledge we acquire within the company by developing at a functional level and use it for third parties too. The boundary between the foreground knowledge of ASML and our background knowledge is still somewhat diffuse. The fact is that ASML has made a conscious decision to transfer knowledge and skills to us which we can use more widely, precisely to enable us to enrich them with experiences elsewhere. And of course also to reduce the development costs for the wafer handler by allowing us to use that experience for the benefit of other customers.’ However, the final objective has not yet been achieved, notes Bambach: ‘We are now the only supplier with that knowledge of wafer handlers, so it is understandable that ASML still wants to have detailed financial control. But that is a question of time – trust needs to continue to grow on both sides. Our objective is to grow towards a position like that enjoyed by Zeiss SMT. Towards the type of partnership you already see in aircraft manufacturing. There, an OEM like Boeing has the know-how regarding the overall architecture of the aircraft and sufficient knowledge about matters such as the landing gear, the cockpit and the engines in order to be able to specify its requirements towards specialists such as Rolls-Royce.’

Semi-productisation

Over a year ago, Festo revealed that it was an OEM white box supplier for a number of large technology firms in the Eindhoven region for various technical solutions. According to managing director Dennis van Beers and senior project consultant Max van den Berg, this has resulted in a much closer partnership which takes shape early on in projects. Van Beers: ‘In relation to the White Paper by Praetimus, we find that Festo increasingly implements the projects in the ‘semi-productisation’ phase. Our larger OEM customers are keen for us to do that. However, full-productisation is a further step, in effect a virtual integration of supplier and customer.’ Festo is not at that stage yet, explains Van den Berg. ‘That will require a stronger basis of trust.’ Van Beers explains: ‘Both parties need to share facts that would never normally be revealed.’ Van den Berg: ‘If you are working that closely with customers on projects, you also need to make solid agreements about the costs. That is not always easy, but once those arrangements are in place, you don’t have to keep on having the same discussions about the price.’ There is still a discussion to be had about the intellectual property. ‘Broadly speaking, the background knowledge we contribute and build up during the project is for us and the foreground knowledge which is in the system drawings belongs to the customer. But if

we want to use certain know-how for a customer in a different sector, they are always open to discussing that.’ Festo likes the role of OEM white box supplier and that is not just because of the margins, assures Van Beers: ‘We are always looking for the market leaders in their segment. We want to build up deep, long-term relationships with them. Because it’s also about the technology. We learn from our customers – and our customers learn from us – and we can use that knowledge and experience to benefit all our activities. This form of partnership is also a subject for discussion with other firms in the Eindhoven region.’ The fact that Festo Nederland, as part of the global Festo conglomerate, is entering into this type of relationship with customers is no coincidence. ‘We secure a relatively high and indeed growing percentage of our turnover from customer-specific developments that call for deep relationships and an acceptance of mutual dependence.’

Ongoing discussions

The NTS-Group is also in discussions about its role with several customers – with ASML about the OEM white box role for the reticle masking unit, a mechatronic diaphragm; and  with another customer about the OEM black box role for a print module for which NTS holds the intellectual property rights. CEO Marc Hendrikse: ‘For an OEM, a printer is of far less interest than the substrate and the resin. Because it can earn its money with the ‘paper and ink’. So it makes sense to outsource all development and manufacturing activities to a party like us.’NTS is on the road to that status of OEM white box and OEM black box supplier, but it has not achieved those positions yet, says Hendrikse, one reason being that the discussion about the ownership of the intellectual property is still ongoing. ‘If we develop a mechatronic module, naturally we do not want to run the risk of being unable to earn back the investment because our technology gets copied and marketed by a third party. Another factor is that customers could become more dependent on us, which makes them cautious. Then there is the question of who will offer the guarantee. If a product becomes defective due to a manufacturing fault on our part, we will repair it. But if that means a factory has to halt production, who will pay for the consequential loss? Making sound agreements with the customer about matters like these takes time.’If NTS does secure the position of OEM white box/OEM black box supplier, one consequence will be that it will have to start doing product marketing. But it does already have some experience in that regard. ‘For example, the print module will contain customer-specific elements, but the basic construction is always the same. The generic know-how it incorporates, for example relating to the right moment to make resins coagulate or liquefy, is something we have to develop and maintain ourselves. It is therefore up to us to ensure that we remain up-to-date with the latest technology and market demands and translate those things into our own products and technology roadmap and product marketing activities.’

with another customer about the OEM black box role for a print module for which NTS holds the intellectual property rights. CEO Marc Hendrikse: ‘For an OEM, a printer is of far less interest than the substrate and the resin. Because it can earn its money with the ‘paper and ink’. So it makes sense to outsource all development and manufacturing activities to a party like us.’NTS is on the road to that status of OEM white box and OEM black box supplier, but it has not achieved those positions yet, says Hendrikse, one reason being that the discussion about the ownership of the intellectual property is still ongoing. ‘If we develop a mechatronic module, naturally we do not want to run the risk of being unable to earn back the investment because our technology gets copied and marketed by a third party. Another factor is that customers could become more dependent on us, which makes them cautious. Then there is the question of who will offer the guarantee. If a product becomes defective due to a manufacturing fault on our part, we will repair it. But if that means a factory has to halt production, who will pay for the consequential loss? Making sound agreements with the customer about matters like these takes time.’If NTS does secure the position of OEM white box/OEM black box supplier, one consequence will be that it will have to start doing product marketing. But it does already have some experience in that regard. ‘For example, the print module will contain customer-specific elements, but the basic construction is always the same. The generic know-how it incorporates, for example relating to the right moment to make resins coagulate or liquefy, is something we have to develop and maintain ourselves. It is therefore up to us to ensure that we remain up-to-date with the latest technology and market demands and translate those things into our own products and technology roadmap and product marketing activities.’

Step by step

Step by step

There are also legal implications, and therefore risks, associated with the position of OEM white box or OEM black box, notes Taco Huizinga of The Law Factor. ‘If you are an OEM black box and you are responsible for and own the complete design of a module, you are also liable if something goes wrong throughout the entire life cycle. It is not enough to do some re-engineering; you have to pay for and assure the repairs and consequential loss. You are also liable for infringements of intellectual property rights held by third parties and for compliance with all kinds of statutory provisions – and for the consequences of any failure to deliver on time. After all, your customer can say: ‘It is your design, your development and production process, on which I have no influence, so you are completely responsible for it.’ On the other hand, it is your intellectual property and, if it is good, your customer will pay you for taking all that responsibility.’ As an OEM white box, the supplier shares those responsibilities. ‘In that situation, the production-related knowledge lies with the supplier, but the product-related knowledge remains with the customer. Who exactly bears the risk in this case will depend entirely on the exact agreements made. It may be that the product-related intellectual property is transferred from the customer to the supplier in a step-by-step fashion, so that the latter can use it to make products for other customers in other domains. This also means the responsibility and risks gradually shift to the supplier. As do the margins.’

Taking over

Paul Schuurmans of Praetimus doubts whether Dutch suppliers will be able to take that step to build-to-roadmap supplier any time soon. ‘You see big foreign firms like Festo, companies with their own roadmap which derive the major part of their turnover from standard components, investing more and more in developing and marketing ever more complex modules at their country sites. It would not surprise me if a company like that were to take over one of the larger Dutch system suppliers. They are of course capable of assuming that build-to-roadmap position.’

Success ‘temporary’

Fellow suppliers are choosing to become OMMs (OEM white box or OEM black box), but that is not the role which Edward Voncken, head of KMWE, is aiming for. ‘That role does  not suit us. We are a typical process specialist-plus, a world leader in particular metal machining steps with associated assembly and engineering services. If we decided to market our own e-bike or blood analysis device, for example, we could become a competitor to our own customers. I see a number of suppliers growing towards that kind of role by ‘productising’, i.e. turning a module into a product which is more or less their own, encouraged by OEMs who want to shift greater responsibility for development, production and maintenance to the chain. But that means taking on a large number of new activities: marketing and business development, R&D and roadmap development, plus product sales, service and maintenance. And you will have to find a module for which the market is big enough to finance all those extra costs.’Suppose you managed to overcome all those obstacles, success might still prove very temporary, so Voncken believes. ‘Of course large OEMs are keen to place the responsibility for particular modules with an OEM white box supplier – until they realise they are losing the associated know-how and therefore control over the development of those modules; that they are becoming dependent on a supplier that can demand a larger share of the margin on account of its new position. At that point, the OEM may decide to hit the brakes and take back those modules. Module suppliers may acquire the role of OEM white box within strict limits, but OEMs will never permit that know-how to disappear into the black box, unless a module is far enough removed from their core technology.’

not suit us. We are a typical process specialist-plus, a world leader in particular metal machining steps with associated assembly and engineering services. If we decided to market our own e-bike or blood analysis device, for example, we could become a competitor to our own customers. I see a number of suppliers growing towards that kind of role by ‘productising’, i.e. turning a module into a product which is more or less their own, encouraged by OEMs who want to shift greater responsibility for development, production and maintenance to the chain. But that means taking on a large number of new activities: marketing and business development, R&D and roadmap development, plus product sales, service and maintenance. And you will have to find a module for which the market is big enough to finance all those extra costs.’Suppose you managed to overcome all those obstacles, success might still prove very temporary, so Voncken believes. ‘Of course large OEMs are keen to place the responsibility for particular modules with an OEM white box supplier – until they realise they are losing the associated know-how and therefore control over the development of those modules; that they are becoming dependent on a supplier that can demand a larger share of the margin on account of its new position. At that point, the OEM may decide to hit the brakes and take back those modules. Module suppliers may acquire the role of OEM white box within strict limits, but OEMs will never permit that know-how to disappear into the black box, unless a module is far enough removed from their core technology.’

Read Further in Link magazine, South Netherland Special 2016.